Do you want to make sure you get top dollar for a business you’re trying to sell? Then you need to know how to value a business.

Or, are you considering buying a business, and need to know EXACTLY what it’s worth, so you pay that price for it and not a penny more?

If so, you’ve come to the right place.

In this article, I’ll make sure you’re armed with every bit of knowledge you’ll need. That way, you’ll be able to determine how to value a business like a pro. My highly actionable advice could end up saving you THOUSANDS of dollars of your hard-earned money in business valuation.

There are SO many questions to ask when you’re trying to find the value of your business. That’s true whether it’s one you already own, or, one you’re considering buying.

Here are a few questions about business valuation that might be swimming around in your head:

How the heck do I value a business anyway?

How much is MY business worth?

What’s the exact process for valuing a business?

I’ve heard there’s more than one method. Which one do I use?

Now, getting answers to these questions won’t be as easy as ordering an Iced Caramel Cloud Macchiato from the Starbucks drive-thru. But it isn’t rocket science either.

The Challenges of Valuing a Business

Let’s get into the specifics of how to value a business you own or a business you’re thinking about buying. But before we do, it might be a TERRIFIC idea to go over how you determine the value of ANYTHING.

To do that, I’ll have to dust off my copy of Economics 101.

There’s going to be disagreement between buyers and business owners as far as price and business valuation goes. Buyers want a low one, while business owners want a high one.

So, a compromise is inevitable.

The more demand there is for a business, the higher the price will be.

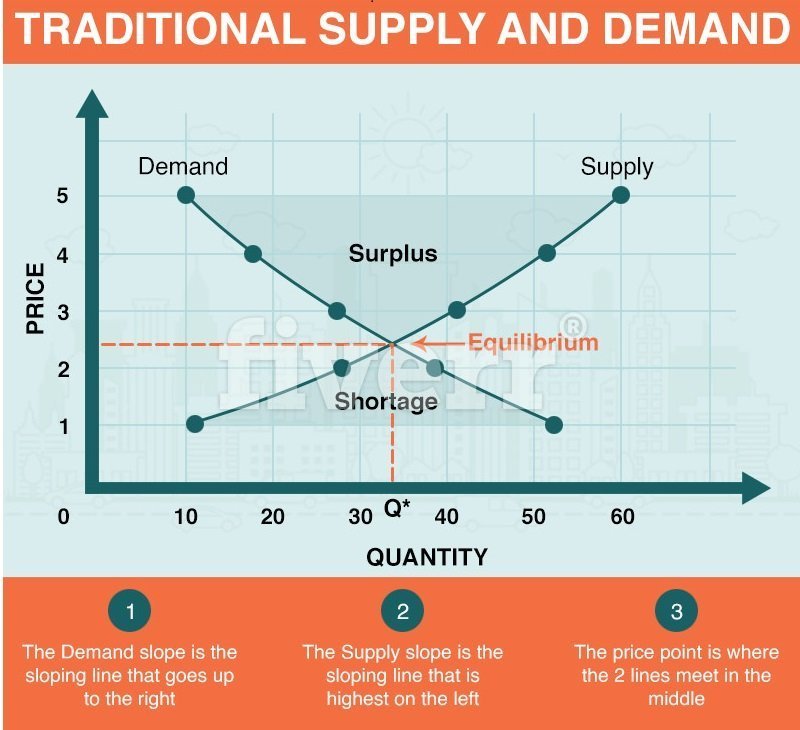

The price for anything is determined by a Supply and Demand Curve. Look at this one:

You arrive at the optimal market price for an item based on supply and demand by figuring out the precise point at which supply equals demand. To do that, you’ll need to create a graph with the supply and demand lines written on it.

Where these two lines intersect is what is called “economic equilibrium,” or the market price for the good or service. Of course, the real value of a good or service is the price a buyer is willing to pay and one that the seller is willing to accept.

For example, suppose we have a can of sweet peas. Let’s say it costs a company 75 cents to manufacture a can of peas.

This cost includes things like:

- Harvesting

- Drying (that’s because they weigh less, so they can more shipped more cheaply)

- Shipping to the processing plant

- Reconstituting them by adding water

- Adding green dye (SURPRISINGLY ENOUGH!)

- Putting them into cans

However, no matter what price he slaps on the can, it will only sell if he can find a buyer willing to pay that price. The buyer could care less about the costs of getting that can to the shelf so he can buy it. He’ll only plunk his hard-earned money down for the peas if he thinks they’re worth it.

What Else You Should Know

This example powerfully illustrates the one thing that’s too often overlooked when pricing a good or service. And that is, value is often (to use an ancient cliché that also happens to be one of the very best “Twilight Zone” episodes ever made), “in the eye of the beholder.”

There must be on the part of the buyer to buy the thing. That’s because a desire is the gasoline that fuels the economic engine that runs the world.

This desire can either be based on needs.

Or, it can be based on wants.

A Tale of Two Cars

Increasingly in today’s world, more consumers are prioritizing wants over needs. Here’s an example. All cars basically do the same thing—get you from Point “A” to Point “B.”

That’s it. A simple function. Even though both cars basically do the same thing, there’s a HUGE difference between the price of a Ford Fiesta and a McClaren P1.

As a matter of fact, about $1,334,740.

Most buyers would consider the P1 to be sexier than the Ford Fusion. In fact, probably about a million times more so.

This desire jacks up the price of the car.

The ONLY way anything has value in the marketplace is if a buyer is willing to buy it. And, at the price that the seller wants. The importance of “want” when it comes to determining value cannot be emphasized enough.

The Power of Emotional Attachment

Real estate is an excellent way to demonstrate this concept.

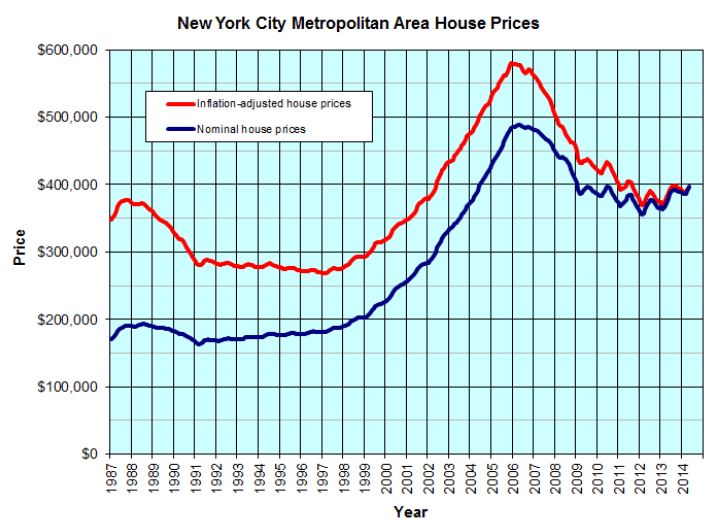

Some of the priciest real estate you could get your hands on happens to be in New York City and San Francisco.

Here are real estate prices in New York:

And here’s what they look like for San Francisco:

However, there’s a certain segment of the population who would not live in either of those two cities.

No matter how low the price happened to be. And even if you paid them to live there.

The same is true for sellers. I recently watched an episode of “Better Call Saul.” In it, Everett Acker (played by the great Barry Corbin), refuses to sell his house to Mesa Verde Bank and Trust. They want his piece of land so they can put a call center on it.

First, they offer him market price for the home. And an additional $18,000.

Then, they increase their offer to market value PLUS $45,000.

But no matter how high the offer goes, Acker won’t budge. That’s because he’s lived there since the 70s. And, he’s emotionally invested in his home. So, because the price is subjective, it can be difficult to determine the price.

People get attached to things, which tends to skew their perception of the thing’s actual value.

I’d Buy THAT for a Dollar

In the real world, we know that people can be enticed into buying something because the price is simply too good to pass up.

For example, with a significant portion of the population, if you offered to sell them a West Village (a fashionable neighborhood in New York City known for its beautiful architecture and chic, artistic offerings) mega-mansion for the unbelievably low price of $1.00, there would be almost no one who would refuse you.

So, price is a powerful motivator. There’s no denying that fact. Even if they don’t really want the item, there are few who can pass up a good deal when they see it. Most people know “great value” when they see it. Nobody needs to tell them!

Whether you’re buying a house or a can of peas, the active market determines price. If people think an item’s price is too high, they’ll flock to a lower-priced alternative. Over time, this causes the price of goods to fluctuate until it achieves economic equilibrium.

How Negotiating Affects Price

However, buying a house is much different than driving down to your local Kroger’s to buy a can of peas. It cost thousands of times more, so there’s a lot more risk involved.

You’re not going to haggle on the price for the can of peas. Everybody who buys a can of peas at the same store will pay the same price for that can. However, negotiating the price of a home is not only allowed—it’s expected.

Because of negotiation, there’s going to be more variation in the price of a house than the price of a can of peas.

Now, you can easily find the average price of a home in a geographical region by checking out tax assessor websites for listings of recently sold homes. Or, call a real estate agent and ask for a list of recently sold properties in the neighborhood you’re looking at.

You could even use a website like this:

For example, if 20 houses sell during the same month and they’re comparable, then a quick calculation will tell you the average price for a home in that neighborhood.

Now, this is all well and good when the market is active. Inactive markets are another story. This is where there are either no sales or no comparable sales.

When Comparisons Become Meaningless

If these 20 homes sold over five years instead of a more limited period, there would be no way to compare one sale with another. That’s because the sales were spaced out over a long time, and comparison becomes meaningless.

The same issue pops up with business sales. The problem is even worse because there are far fewer sales of a business in a location than home sales. And because of this, looking at comparable sales to determine value when thinking about buying a small business is less useful.

However, because realtors are used to comparing properties when determining value, they continue to use this same method when trying to figure out how much a business is worth. The real problem with this is that there’s no practical way to compare one company with another.

A hair salon is a whole LOT more different than a machine part manufacturer. Even if you compare one kind of restaurant with another, there are still a lot of differences between the two.

A Tale of Two Cafés

For example, in the area where I live, there are two vegan cafés. Now, you might think that since both are vegan, that you can easily compare one to another when you’re trying to figure out what the price of a vegan café is in the area.

But you’d be wrong.

That’s because one café took over space formerly occupied by a late-night dive restaurant. You know the kind of place:

The kind you go to in the middle of the night after having one too many Long Island Iced Teas at your favorite bar. The vegan café retains a bit of this grungy charm. It’s located in a somewhat rough part of town, right next door to a minor league baseball park.

The second café occupies space that used to be a street-front slaughterhouse and restaurant specializing in buffalo meat (which is a funny place for a vegan diner to occupy). It’s ten times ritzier than the first joint. And, it’s located in an upscale part of the city, right next to several colleges.

Here’s what its website looks like:

Now, even though the two cafés are vegan establishments, saying that their value is going to be comparable is a silly exercise in futility.

SO, DON’T EVEN TRY IT, MISTER!

The Goodwill Factor

Finally, you’ll need to consider “goodwill” when trying to figure out how much a business is worth. Goodwill is the intangible assets of a company.

Assets of the tangible variety are easier to understand. For example, let’s consider a manufacturer that makes phone cases that uses plastic to build her cases. The value of this raw material is wicked easy to figure out.

However, suppose that this maker has a highly secret, super-efficient, patented process for making these cases. Trying to ascertain the monetary value of this technological trade secret is going to be challenging to determine.

Yet, this process is a significant asset of the company because it supercharges its competitive advantage. Intangible assets are often overlooked when someone is conducting a valuation. That’s because they’re:

- THOUGHTS

- IDEAS

- CONCEPTS

- EXPERIENCES

And other things that might seem nebulous and indefinable, but which rake profit in for the company. How the heck can you slap a dollar amount on items like this? It’s well near impossible—even for professional consultants who have been doing this kind of thing for decades.

B.Y.O.A. (Bring Your Own Assets)

Sometimes, a potential buyer of a small business isn’t acquiring an intangible asset. Instead, they’re contributing an asset to the company they’re buying.

For example, say you purchase a company because you absolutely adore their product. However, you’re not so crazy about their production facility. That’s because it’s seen better days and doesn’t have all the technological bells and whistles that your own facility has.

These are processes you spent years developing. And without all the high-tech wizardry you perfected over the years on your own products, there’s no way you’ll be able to competitively price the good.

So, you start making the gadgets at your own factory. You just made the value of the small business you bought skyrocket into the stratosphere because of the intangible assets you added to it.

These examples illustrate why there are so many challenges in determining the value of a small business. Next, we’ll look at formulas you can use to help figure out how much a company is worth. However, keep in mind that each one will only give you a rough idea because of all the subjective factors we just talked about.

Business Valuation Formulas

There are several methods for determining the value of a business. Here’s are some of them:

Asset-Based Method

One of the easiest ways to for business valuation is something called the asset-based method. As you might guess from the name, what you do is add up all the business assets. Although they’re going to be mostly tangible assets, there might be a few intangible assets you’ll have to take into consideration.

Here’s how it’s actually done:

After you list all the assets, you’ll next have to list all the liabilities. These are things like debts and accounts payable. Then to come up with a ballpark figure for the value, subtract the liabilities from the assets.

Here’s an example.

A company has the following assets:

- $20,000 CASH

- $130,000 BUILDING

- $25,000 FLEET VEHICLES

- $25,000 INVENTORY AND MACHINERY

Total assets are $200,000.

Now, let’s list their liabilities. These are:

- $85,000 MORTGAGE

- $17,000 WORKING CAPITAL LOAN

- $40,000 ACCOUNTS PAYABLE

The company would have a total asset base of $200,000. Total liabilities would be $142,000. Thus, the company would have a value of $58,000.

Of course, these numbers are a snapshot of a specific moment in time. The only problem with that is that business valuation is always fluctuating. For example, what if the day after this snapshot was taken, the company was lucky enough to snag a much-coveted account.

And, this brand spanking new client paid a hefty retainer fee.

Admittedly, this sudden influx of both new business and cash will increase the value of the company. Almost every day, something could happen that could either increase or decrease the value of the business.

So, it’s hard to keep track of a company’s ever-changing value when asset-based valuation is all you use. That’s why most experts recommend using it only as a starting point.

Revenue Model Valuation Method

Next is the revenue model business valuation method. This method is comprised of several different approaches, all lumped in together because they determine the value of a business based on its income. What’s great about this strategy is that it reflects actual business operations.

What could be a better metric of the value of a business than that?

It’s easy to see why this might be a better method to figure out how much a small business is worth than the asset-based approach. And really (when you come right down to it) this is simply a valuation based on the sales of a company.

So how does this system work? Well, the details are where the weaknesses of this methodology can be seen. Let’s look at an example:

Say a hair salon has been open for 20 years. Their yearly revenue currently happens to be $250,000. The owner makes a profit of about $75,000. A formula solely based on sales would take the $250,000 and say this is the business’s value.

However, these figures deserve a little more scrutiny. Let’s say the $250,000 is the smallest gross revenue the company has earned in its two decades of existence. This means that cash inflows are declining over time.

Is that an excellent value to place on the small business? It probably isn’t, if revenues are going to continue to drop each year. That’s why a revenue model valuation (although it has certain advantages over asset-based valuation) might not tell the whole story.

How Accurate is Revenue Model Business Valuation?

So, I just pointed out several flaws in the revenue model of small business valuation. There are so many variables that can affect a company’s revenue stream. For this method to be accurate, you must account for them all somehow.

Here’s another variable: there could be stylists who are rock stars. However, they’ve only been with the salon for a year or two. During that time, sales skyrocket because of their extraordinary ability to give everyone exactly the hairstyle they always dreamed of.

But now they’re gone. The salon is left with beauticians of a more average sort. Because of this, the revenues of the business drop precipitously.

Or, let’s pretend that the business sells machines that do emission testing. In this scenario, several states drastically increased their emission standards. This has the effect of rendering the old devices obsolete.

When this happens, automotive repair shops that issue inspection stickers are all scrambling to get their hands on the new machines. This sends the revenues of the company making the machine through the roof.

But the next year, sales level off, because all automotive places that issue inspection stickers already have the newer models. As you can see, the revenue-based valuation method’s major problem is that it’s only a snapshot of the company at a moment in time.

Discounted Cash Flow

So, that’s two ways to determine small business valuation.

Is there another?

Turns out there is. But before we go over these other methods including discounted cash flow, let’s look at one of the most prominent investors in the world. You’ve probably heard of him.

Warren Buffet.

His company, Berkshire Hathaway, has built a HUMONGOUS empire of businesses all over the planet. They include:

Mr. Buffet acquired a controlling interest of more than 10% in every one of these companies because he’s a buyout artist par excellence. He wouldn’t have added these companies unless, over the years, he honed his ability to determine value to a razor-sharp point.

Here’s the point in the festivities you might be asking:

NOW, WHAT THE HECK VALUATION METHOD DOES WARREN USE?

Good question. The answer is discounted cash flow analysis. This is a more accurate method than the other two methods we discussed. That’s because cash flow doesn’t use a mere moment in time—it uses a more extended period. Which is usually several years.

Most non-discounted methods for determining value are based on financial history. However, you’re not purchasing a book talking about the company’s past achievements. You’re buying their financial performance because you want to benefit from their future cash flow.

Now, you might be thinking that past financial success is a good predictor of future economic success. But just like admen in slick financial product infomercials will tell you, you’d be wrong.

And that’s because the future is fraught with uncertainty, my friends!

When you use the cash flow method, you’ll be comparing the rate of return you’d get on this company to the rate of return for U.S. Treasury bills. To do this, use the formula for the Net Present Value of Money.

In this formula, cash flow is the money flowing in and out of the company. R is the discount rate. This can be a percentage. For example, the current interest rate.

Alternatively, you can use the weighted average cost of capital for your percentage. This is the rate a company pays to finance its assets. It includes the average cost of a company’s working capital after taxes.

N is the time period. You can use however long you want for this amount, whether that’s 5, 10, or 30 years.

The number you get after you input all values into the formula is called the terminal value. This represents the growth rate for projected cash flows for years other than the time parameters you’re using.

To figure out this value, take the cash flow of the final year. Then, multiply it by (1+long term growth rate in decimal form) and divide it by the discount rate minus the long-term growth rate in decimal form.

Say you want to do a discounted cash flow analysis of a business you’re considering buying. First, estimate its future cash flow. To do this, look at the balance sheet for the previous year. This is the amount of revenue that flowed in and out of the business.

Let’s say this figure was $750,000 in 2019. Now, you can look at the number for 2018. Say this number is $700,000.

Now, we’ll have to calculate the rate of growth. To do that, use this formula.

Plugging in the numbers from our example, this would be:

GROWTH RATE = $750,000-$700,000/$700,000 = 7.14%.

Use this to estimate the future growth rate. Using this number, we extrapolate that our company will grow by this amount for the first two years. And then, in the next two years, we take all factors into consideration and estimate that growth will slow to 6%.

You also need to choose a percentage to calculate the terminal value. This number represents the long-term growth of the company. Err on the side of caution with this, so your estimate isn’t overly optimistic.

A good guideline is to use current interest rates for this amount. Let’s say it’s 4%. With these figures, you can now calculate the projected cash flow for each year in your timeframe.

Lastly, we need to figure out the weighted average cost of capital. Here’s the formula.

Let’s say the discount rate for our company is 4%. Now, let’s plug our numbers into the first formula to get the discounted cash flow for the small business:

($803,550 / 1.041) + ($860,923.47 / 1.042) + ($912,578.88 /1.043) + ($967,333.61 / 1.044) + ($1,006,026.95 / 1.045)

= $772,644.23 + $827,811.03 + $877,479.70 + $930,128.48 + $967,333.61

BUSINESS DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW = $4,375,397.05

So, this is the value of the company using the Discounted Cash Flow Method.

Come Up with A Range of Values

The best way to come up with an accurate valuation is to use all these methods to come up with a range of values. Combining the asset-based approach with the revenue model valuation method and discounted cash flow will help you get a clearer picture of the business’s actual value.

As an example, let’s presume there is a restaurant getting ready to be placed on the market. The company has been averaging $200,000 in revenues for the last 10 years. In the previous three years, the owner has not been as involved in the company.

So, the earnings are below average. The assets of the company are as follows:

- BUILDING $250,000

- EQUIPMENT $15,000

- FIXTURES $10,000

- CASH $25,000

The debts are:

- $10,000 MORTGAGE

- WORKING CAPITAL LOAN OF $25,000

In the most recent year of revenue, the company earned $95,000.

From the revenue model, the value is $95,000.

From the asset-based method, the value is $300,000.

From the discount cash flow method, the value is $448,622.

The range method then would say that the value of the company would be somewhere between $95,000 and $448,622. The owner and buyer could add in other factors to adjust this range, like their opinion of the small business.

Conclusion

What is the bottom-line in finding a value to a small business? The best answer is that it is complicated.

First, value is often in the eye of the beholder. So, value can be subjective, based on personal opinions.

Second, there are multiple methods for determining value—whether that’s the asset-based, revenue model, or discounted cash flow method. Each has merit, but each has its faults. This means that there is no perfect method for determining the value of a business.

That‘s why the best solution is to use a range of value to place you in the “ballpark” for what a small business is worth. This range provides for more accuracy in assigning value.

I hope this article has instilled you with the confidence to make excellent business valuations.